Instead of rolling out of bed and somewhat sleepily opening your emails in your living room, let’s imagine you’re in Dublin and you’re late.

In your hastily tied dressing gown, you follow me as I walk (or rather jaywalk) through the city centre; Jaysus will she ever slow down.

Deep into the Liberties we go; you dodge still burning cigarette embers in your fluffy slippers while gawking at old brick buildings.

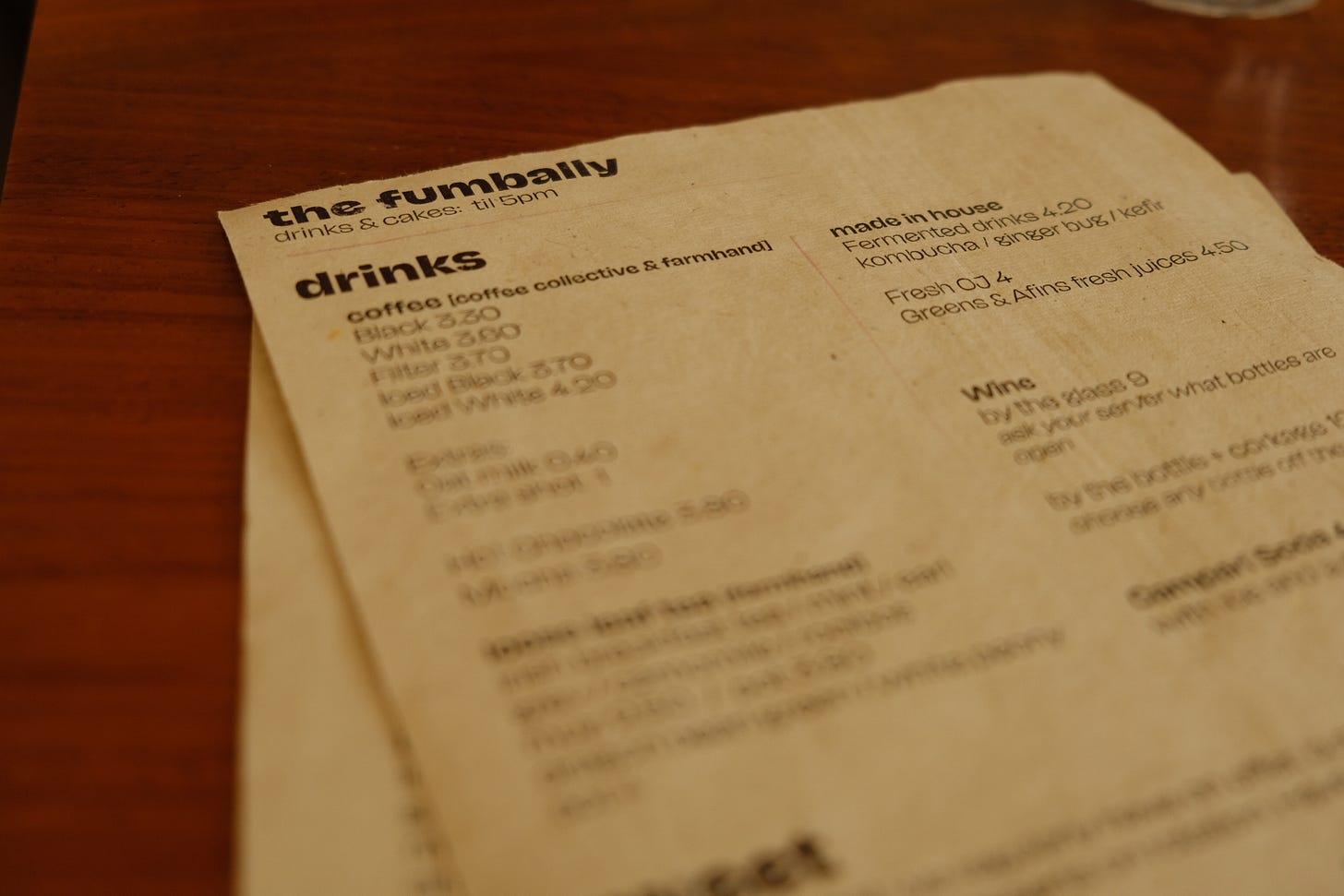

I dive into a little cafe, you almost loose me.

Half expecting to be thrown out, you look timidly around the room and spot a guy knitting quietly in the back corner.

You order a coffee and grab a seat nearby so you can eavesdrop.

The conversation begins.

The first thing you notice about Conor O’Brien is how young he is; the second thing, how old he is.

The 21-year-old knitwear designer sits with one sprained ankle in the past as he cables away the morning & one foot firmly in the future, as he discusses his ambitions while politely ignoring Tinder notifications.

It is a curious thing to be young in an industry almost exclusively comprised of older people; for example, O’Maille’s of Galway employ numerous hand knitters over the age of 70, with the recent addition of two young wans in their forties.

He simultaneously relishes and rejects the weight of keeping traditions alive, preferring to think of wool as his chosen medium with which to create wearable art.

A budding expert in creative problem solving, he produces single size, loose fitting designs which he would personally wear.

‘I love boxy shapes, which are not shapeless, but not tailored either.’

Conor avoids following trends or, as he describes it, creating what the virtual world deems worthy. He points out that tailored garments, though custom made, are not necessarily sustainable, as the item is unlikely to fit anyone else.

In contrast, his minimalistic designs are meant to be handed down.

Inspired by great Parisian designers like Christian Dior and Jacques Fath, Conor originally dreamt of becoming a master tailor and entered fashion school with an already defined vision of muted shades and structure.

His NCAD tutors asked that every student learn their way around a hook and needle, but Conor, not apt to do things by halves, found a distant relative who happened to be an expert Aran knitter. Between lockdowns, they had intensive 1:1 lessons, which were complicated by the fact Conor is left handed, his teacher was not. Every technique had to be mirrored, which might explain why he can’t find a term for his style of knitting.

His is a story littered with kindly cousins and uncles, artistic psychopomps which seem to be sorely lacking in many a modern day life.

After creating innumerable Aran scarves as gifts and wildly unpriced commissions, he tackled his first sweater (‘it was an absolute nightmare’) and then started working in Beautiful South, a boutique store in Rathmines owned by his second cousin. The neutral toned classic pieces with a modern twist in-store fed into his burgeoning philosophy of knitting and style.

‘I think since working in a boutique and coming in contact with brands like Maison Margiela, I have a real obsession with avant-garde clothing, which is very designed but still very wearable & practical.’

Though he occasionally uses patterns for complex collars and shaping, ‘the way I was taught to knit gave me the liberation to design in blocks’; blocks referring to sections of textured stitches to create an overall garment.

There is a dual practicality to his minimal designs; garments must be simple to highlight the heavily textured Aran stitches and functional to be worn everyday.

‘With the gilet or the sweater I’ve just recently produced, you can throw that on and go for a hike, you can garden in it, and you can wear it out.’

Presumably descended from the High Kings of Ireland, O’Brien is quite comfortable in the luxury boutique setting.

‘I love meeting customers directly, establishing a relationship. The whole store is a space dedicated to you trying on clothes.’

Having honed his personalised approach to fashion, he has started to develop a dedicated clientele and is now leaning heavily on a made to order model, reminiscent of the early days of haute couture.

‘I have the phone numbers of clients and sometimes ask if they’re around town for a coffee.’ This isn’t a one way street though; in stark contrast to faceless e-commerce conglomerates, his personal phone number is on his clothing tags.

Conor brings that personal touch to his social media presence too.

Like many creatives, he spends considerable time creating an aesthetic which is simultaneously clean and reflective of his brand’s direction. Too clean and it becomes editorial & distant; too reflective and there is no longer space for the customer.

Partly due to a self confessed lack of patience, Conor has started to photograph his own work. One day, he borrowed his brother’s camera, let the landscape do the talking and et voila… a beautiful moment of truly circular fashion was captured. The wool had returned to the wild.

Treading a fine line between transparency and word salad, he prefers not to share prices on social media, reasoning that the work required to find the price will weed out impulse buyers.

Though boutique stores (and almost everyone else) works on a seasonal model of clothing collections, Conor believes that approach is far from optimal.

‘I’m always asked ‘when is your next collection?’. There’s no such thing as far as I’m concerned. The question is ‘when is the next garment out?’’

He has strong words for an often toxic fashion industry and seeks to distance himself from commonplace unsustainable practices.

‘[It] drives me mad when fashion graduates come out with highly avant grade collections to the extent the pieces are literally going to be shoved in a wardrobe or archive to be displayed here or there. The big colleges are pressuring people to be sustainable while cooperating with a corrupt industry.’

Ironically Conor is starting to get noticed by the industry he eschews.

Styling consultants Aya Studios styled Conor’s Aran gilet in a photoshoot with the Dublin rapper Malaki; the results were a refreshing interpretation of Aran knitwear; good God, someone with a shaved head and barbed wire tattoos wore cables!

He has a number of other photoshoots coming up, which explains the café knitting. Once again, close relationships with clients comes in handy, as he can text them to borrow finished pieces for shoots, partially solving the perennial stock problem.

O’Brien is surprisingly confident, not nearly as fragile as one might assume a young designer to be.

He openly discusses pricing, business models and challenges.

‘As a freelancer, it’s a blessing and a curse to blur the lines between life and work, especially when you’re up knitting at 5am for work when you should be asleep. It’s a unique experience, it still flabbergasts and excites me.’

Business is going well, but even a modicum of success brings new issues; new level, new devil as the saying goes. He already has two knitters ready to knit the bulk of his time-consuming designs. At this stage of busyness, it would be a relief if his Paglia-inspired essays got him thrown out of college.

Harkening back to a time of instinctive creation inspired by demand, Conor considers true luxury to be the home knitted sweaters of rural Ireland pre-electrification.

(His favourite documentary series is ‘Hands’, which profiled crafts in 1970s Ireland.)

He raves about homespun yarn and rages at the difficulty of finding wool with lanolin still in it.

Always on the lookout for new materials, Conor keeps a keen eye on indie spinners and dyers in Ireland, looking for natural fibre yarns uniform enough to be used in clothing.

He has several items in his Etsy basket, including a nettle yarn from India (ever seen how many nettles there are in Tipperary?).

He dreams of Aran weight organic cotton and hemp yarns, or even pure Irish wool.

We talked at length about the curious hush-hush nature of sourcing wool in Ireland; inevitably all roads lead to the indubitable Maureen at Donegal Yarns.

Speaking of Donegal, that is the place in which the Dublin rebel, like others who shall remain nameless (cough cough), feels most comfortable. ‘If there were a train to Donegal, I’d be there every weekend!’

Conor would love to talk shop with other designers, but conscientious young artists have a strict self-imposed code of ethics and rigorously avoid plagiarism, a hallmark of slow fashion if there ever was one.

In spite of living in an era of wishy washy global citizen initiatives, Conor is fiercely Irish.

When I asked him if his future plans include a one-way trip to Dublin Airport, he laughed and said ‘Every creative in Ireland is exported to make more money and frankly I don’t appreciate it.’

He speaks with great enthusiasm about Japanese designers (stay tuned for the Aran kimono) and the anti-fashion minimalism of the Antwerp Six, but he believes strongly in Irish designers, like Cleo Prickett.

In his opinion, there needs to be a general celebration of contemporary Irish artists and designers within Ireland, so young creatives can avoid the fate of Ib Jorgenson and Sybil Connolly, who are renowned everywhere ‘except here’.

Rather than waiting for validation from US and European media, as is traditional within Ireland, O’Brien asks why we don’t simply provide our own recognition.

‘Why aren’t weekly exhibitions of different Irish designers on rotation in the National Museum?’

Conor developed a taste for exhibitions after a chance meeting with stylist Suzanne Whelan led to an invitation to take part in an Irish design showcase. The exhibition was held at the new Arthaus hotel in Dublin, which created cocktails in each designer’s honour.

O’Brien plans to contribute to a new Dublin fashion scene with exhibitions and events featuring local designers.

‘I love collaboration and exchanges with other artists.’

(He walks the walk too; while wearing a necklace from Capulet and Montague, one of his favourite Dublin based jewellery brands, he constantly suggests other creatives for me to interview.)

Inspired by Tokyo concept stores and Dover Street pop up shops, Conor envisions a more sophisticated approach to fashion retail without becoming snobbish, or even worse, bureaucratic.

His own boutique, perhaps?

Ideally yes, but he is unsure if this is a necessary step. He would eventually like to stock his pieces in various stores across Ireland, and perhaps only in Ireland.

‘I like the idea of a product being from Ireland and not available anywhere else.’

When asked where he is happiest, O’Brien smiles.

He loves to spend an afternoon on Drury street, popping into stores like Jenny Vander, Om Diva and the Irish Design store, before heading to a cafe which uses local produce.

Oh and the mountains.

‘Everything about my designs is reaffirmed by being out in nature.’

But, in truth, where Conor is happiest is not a where, but a when; at 5am, when he has completed the last stitch in a new sweater.

As the interview (and the sleeve he’s knitting) winds up, he says:

‘To answer your question, I don’t plan on moving out of Ireland. I’d love to have some gorgeous cottage in the country, get a car and have my studio there.’

His long-term plans align surprisingly well with what makes him happy.

A good omen indeed.

You can find Conor on Instagram @conorobriendesign; his designs are available at Beautiful South, a luxury boutique store in Rathmines, Dublin 6, Ireland.

Dr Aoife Long is a fashion writer by night and a creative director at Spirit and Luxury by day.